Ready for tailored PhD help? Talk to our PhD-qualified team today and get expert support for your thesis, proposal or career transition. See all PhD services here.

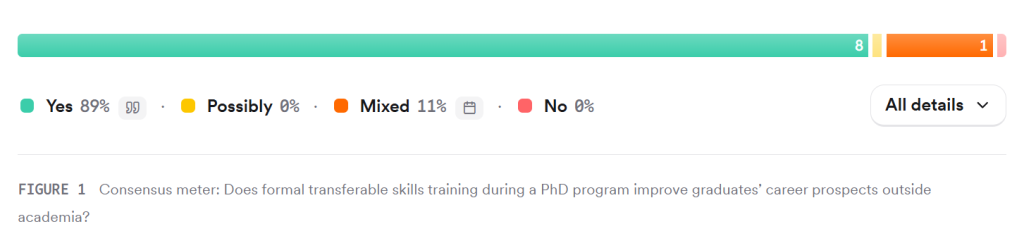

Formal training in transferable skills during a PhD program is associated with improved career prospects outside academia, especially when training is structured, targeted, and aligned with industry needs.

1. Introduction

The increasing diversification of PhD career trajectories has prompted a shift in doctoral education toward the development of transferable skills—such as communication, project management, teaching, and entrepreneurship—to enhance employability beyond academia. Multiple studies and program evaluations indicate that structured, formal training in these skills not only broadens career awareness and readiness but also aligns doctoral graduates’ competencies with industry demands, thereby improving their prospects in non-academic sectors (Sinche et al., 2017; Roy, López and Álvarez, 2025; Lindsey et al., 2024; Ashonibare, 2022; Layton et al., 2020; Mitic and Okahana, 2021; Salm and McKinney, 2024; Main, Wang and Tan, 2021; Brandt et al., 2021; Miliotis et al., 2025). While traditional PhD programs have focused on research and discipline-specific expertise, there is growing evidence that integrating transferable skills training—through courses, workshops, internships, and professional development modules—can bridge the gap between academic preparation and workforce requirements (Sinche et al., 2017; Roy, López and Álvarez, 2025; Ashonibare, 2022; Mitic and Okahana, 2021; Salm and McKinney, 2024; Stamati and Willmott, 2022; Brandt et al., 2021; Miliotis et al., 2025; Nguyen, 2024; Brandt et al., 2025). However, gaps remain in the consistency, recognition, and practical application of such training, and some barriers persist, including limited awareness of non-academic career options and insufficient networking opportunities (Sinche et al., 2017; Ashonibare, 2022; Ganapati and Ritchie, 2021). Overall, the literature supports the value of formal transferable skills training in enhancing PhD graduates’ employability and satisfaction in diverse career paths.

Figure 1: Consensus meter: Does formal transferable skills training during a PhD program improve graduates’ career prospects outside academia?

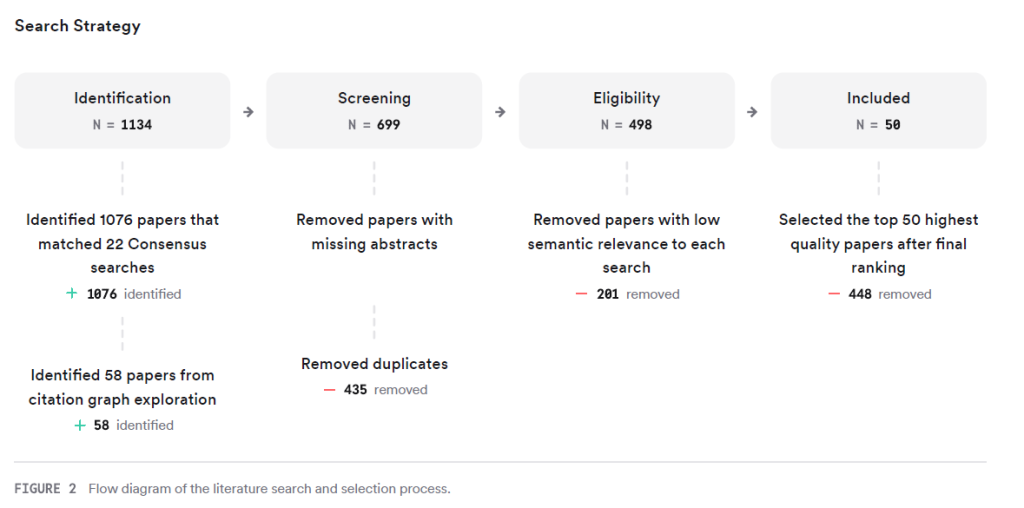

2. Methods

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across over 170 million research papers in Consensus, including sources such as Semantic Scholar and PubMed. The search strategy involved 22 targeted queries grouped into 8 thematic clusters, focusing on the causal impact, models, critiques, and interdisciplinary perspectives of transferable skills training in doctoral education. In total, 1,134 papers were identified, 699 were screened, 498 were deemed eligible, and the top 50 most relevant papers were included in this review.

| Identification | Screening | Eligibility | Included |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1134 | 699 | 498 | 50 |

Figure 2: Flow diagram of the literature search and selection process.

Eight unique search groups were used, covering causal impact, program models, critiques, and adjacent constructs to ensure comprehensive coverage of the topic.

3. Results

3.1. Impact of Transferable Skills Training on Employability

Empirical studies consistently show that PhD programs that incorporate formal transferable skills training—such as communication, project management, teamwork, and leadership—report higher employability and job satisfaction among graduates in non-academic careers (Sinche et al., 2017; Roy, López and Álvarez, 2025; Lindsey et al., 2024; Ashonibare, 2022; Layton et al., 2020; Mitic and Okahana, 2021; Salm and McKinney, 2024; Main, Wang and Tan, 2021; Stamati and Willmott, 2022; Brandt et al., 2021; Miliotis et al., 2025; Nguyen, 2024; Brandt et al., 2025). Structured programs, such as the NIH BEST initiative and the SHIFT program, have demonstrated positive outcomes in career readiness, confidence, and successful transitions to industry and other sectors (Sinche et al., 2017; Lindsey et al., 2024; Harris et al., 2025; Woods and Lindsey, 2024; Brandt et al., 2021; Miliotis et al., 2025; Meyers et al., 2016; Brandt et al., 2025; Claydon, Farley-Barnes and Baserga, 2021).

3.2. Types and Delivery of Transferable Skills Training

Transferable skills are developed through a variety of mechanisms, including dedicated courses, workshops, internships, and embedded professional development modules (Sinche et al., 2017; Roy, López and Álvarez, 2025; Lindsey et al., 2024; Ashonibare, 2022; Layton et al., 2020; Stamati and Willmott, 2022; Brandt et al., 2021; Miliotis et al., 2025; Nguyen, 2024; Brandt et al., 2025). Programs that involve industry collaboration, experiential learning, and mentorship are particularly effective in aligning training with workforce needs (Roy, López and Álvarez, 2025; Ashonibare, 2022; Mitic and Okahana, 2021; Salm and McKinney, 2024; Stamati and Willmott, 2022; Rodrigues et al., 2018; Brandt et al., 2021; Miliotis et al., 2025; Nguyen, 2024; Brandt et al., 2025).

3.3. Barriers and Gaps in Training

Despite the benefits, several barriers persist: inconsistent implementation across disciplines, lack of awareness of non-academic career options, insufficient networking opportunities, and limited recognition of transferable skills by both trainees and employers (Sinche et al., 2017; Ashonibare, 2022; Mitic and Okahana, 2021; Ganapati and Ritchie, 2021). STEM fields tend to offer more structured transferable skills training than social sciences and humanities (Ashonibare, 2022; Martins et al., 2021; Cui and Harshman, 2023; Ganapati and Ritchie, 2021).

3.4. Outcomes and Satisfaction

PhD graduates who receive formal transferable skills training report increased career awareness, confidence, and satisfaction in both academic and non-academic roles (Sinche et al., 2017; Layton et al., 2020; Main, Wang and Tan, 2021; Stamati and Willmott, 2022; Brandt et al., 2021; Miliotis et al., 2025; Brandt et al., 2025; Claydon, Farley-Barnes and Baserga, 2021). There is no evidence that participation in such training negatively impacts research productivity or time to degree (Brandt et al., 2021; Meyers et al., 2016; Lenzi et al., 2020).

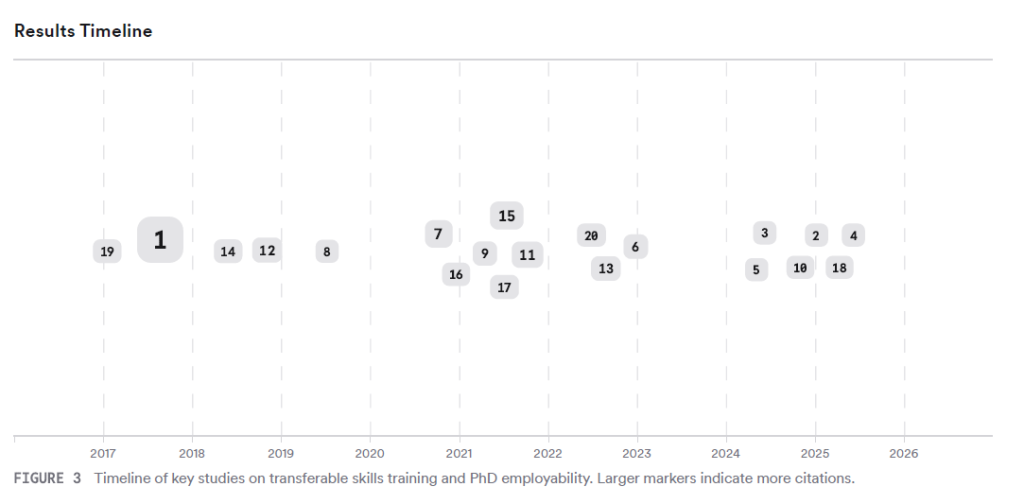

Results Timeline

Figure 3: Timeline of key studies on transferable skills training and PhD employability. Larger markers indicate more citations.

Top Contributors

| Type | Name | Papers |

|---|---|---|

| Author | Patrick D. Brandt | (Sinche et al., 2017; Brandt et al., 2021; Brandt et al., 2025) |

| Author | R. Layton | (Sinche et al., 2017; Layton et al., 2020; Brandt et al., 2021; Brandt et al., 2025) |

| Author | M. Lindsey | (Lindsey et al., 2024; Woods and Lindsey, 2024; Harris et al., 2025) |

| Journal | PLoS ONE | (Sinche et al., 2017; Layton et al., 2020; Steen et al., 2020) |

| Journal | Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education | (Ashonibare, 2022; Mitic and Okahana, 2021) |

| Journal | Physiology | (Harris et al., 2025; Woods and Lindsey, 2024) |

Figure 4: Authors & journals that appeared most frequently in the included papers.

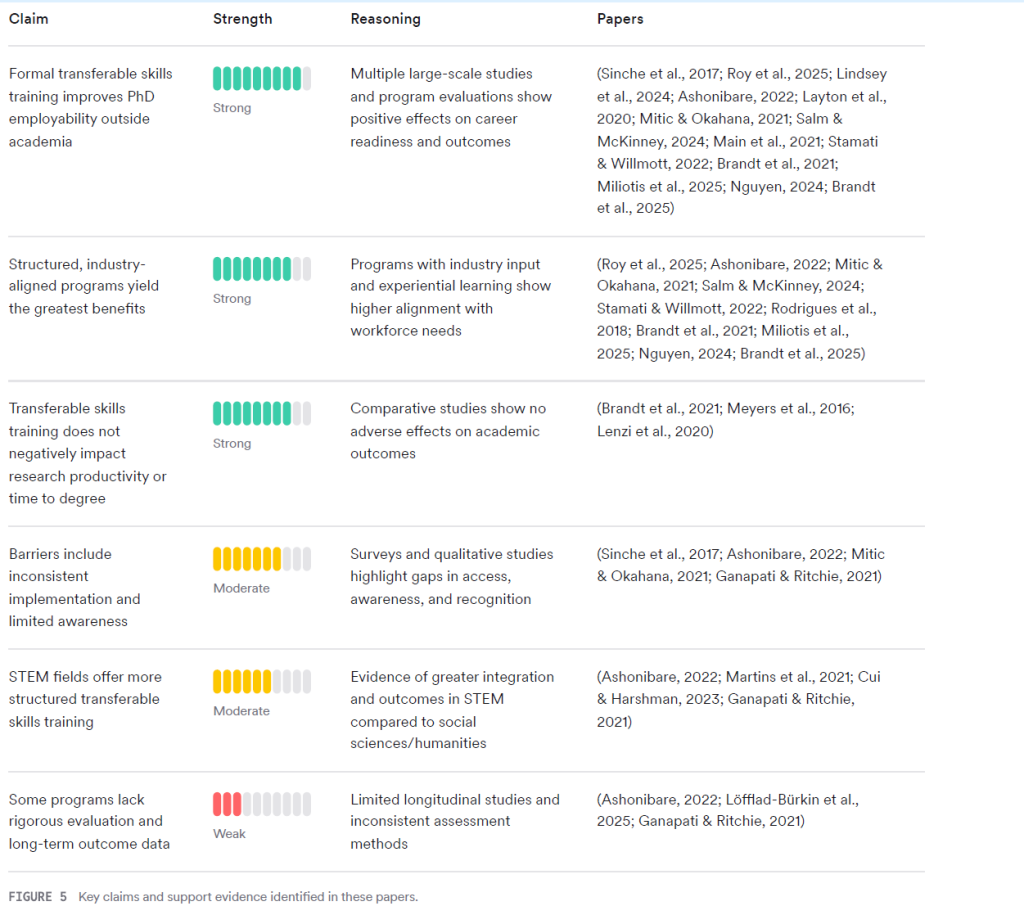

4. Discussion

The literature strongly supports the integration of formal transferable skills training in PhD programs as a means to enhance graduates’ employability outside academia (Sinche et al., 2017; Roy, López and Álvarez, 2025; Lindsey et al., 2024; Ashonibare, 2022; Layton et al., 2020; Mitic and Okahana, 2021; Salm and McKinney, 2024; Main, Wang and Tan, 2021; Stamati and Willmott, 2022; Brandt et al., 2021; Miliotis et al., 2025; Nguyen, 2024; Brandt et al., 2025). High-quality evidence from large-scale surveys, program evaluations, and systematic reviews demonstrates that such training increases career readiness, broadens career awareness, and aligns graduate competencies with industry needs (Sinche et al., 2017; Roy, López and Álvarez, 2025; Ashonibare, 2022; Layton et al., 2020; Mitic and Okahana, 2021; Salm and McKinney, 2024; Main, Wang and Tan, 2021; Stamati and Willmott, 2022; Brandt et al., 2021; Miliotis et al., 2025; Nguyen, 2024; Brandt et al., 2025). Notably, programs that are structured, intentional, and involve industry partnerships yield the most significant benefits (Roy, López and Álvarez, 2025; Ashonibare, 2022; Mitic and Okahana, 2021; Salm and McKinney, 2024; Stamati and Willmott, 2022; Rodrigues et al., 2018; Brandt et al., 2021; Miliotis et al., 2025; Nguyen, 2024; Brandt et al., 2025). However, challenges remain in ensuring consistent access, recognition, and practical application of these skills, particularly in non-STEM fields and among underrepresented groups (Ashonibare, 2022; Martins et al., 2021; Cui and Harshman, 2023; Ganapati and Ritchie, 2021). There is also a need for greater institutional support, faculty buy-in, and ongoing evaluation of program effectiveness (Sinche et al., 2017; Ashonibare, 2022; Brandt et al., 2021; Miliotis et al., 2025; Meyers et al., 2016; Brandt et al., 2025; Ganapati and Ritchie, 2021).

Claims and Evidence Table

| Claim | Evidence Strength | Reasoning | Papers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formal transferable skills training improves PhD employability outside academia | Evidence strength: Strong (9/10) | Multiple large-scale studies and program evaluations show positive effects on career readiness and outcomes | (Sinche et al., 2017; Roy, López and Álvarez, 2025; Lindsey et al., 2024; Ashonibare, 2022; Layton et al., 2020; Mitic and Okahana, 2021; Salm and McKinney, 2024; Main, Wang and Tan, 2021; Stamati and Willmott, 2022; Brandt et al., 2021; Miliotis et al., 2025; Nguyen, 2024; Brandt et al., 2025) |

| Structured, industry-aligned programs yield the greatest benefits | Evidence strength: Strong (8/10) | Programs with industry input and experiential learning show higher alignment with workforce needs | (Roy, López and Álvarez, 2025; Ashonibare, 2022; Mitic and Okahana, 2021; Salm and McKinney, 2024; Stamati and Willmott, 2022; Rodrigues et al., 2018; Brandt et al., 2021; Miliotis et al., 2025; Nguyen, 2024; Brandt et al., 2025) |

| Transferable skills training does not negatively impact research productivity or time to degree | Evidence strength: Strong (8/10) | Comparative studies show no adverse effects on academic outcomes | (Brandt et al., 2021; Meyers et al., 2016; Lenzi et al., 2020) |

| Barriers include inconsistent implementation and limited awareness | Evidence strength: Moderate (7/10) | Surveys and qualitative studies highlight gaps in access, awareness, and recognition | (Sinche et al., 2017; Ashonibare, 2022; Mitic and Okahana, 2021; Ganapati and Ritchie, 2021) |

| STEM fields offer more structured transferable skills training | Evidence strength: Moderate (6/10) | Evidence of greater integration and outcomes in STEM compared to social sciences/humanities | (Ashonibare, 2022; Martins et al., 2021; Cui and Harshman, 2023; Ganapati and Ritchie, 2021) |

| Some programs lack rigorous evaluation and long-term outcome data | Evidence strength: Weak (3/10) | Limited longitudinal studies and inconsistent assessment methods | (Ashonibare, 2022; Löfflad-Bürkin et al., 2025; Ganapati and Ritchie, 2021) |

Figure 5: Key claims and support evidence identified in these papers.

5. Conclusion

Formal training in transferable skills during PhD programs is strongly associated with improved career prospects outside academia, especially when such training is structured, industry-aligned, and supported by institutional resources. While the evidence base is robust, ongoing challenges include ensuring equitable access, consistent implementation, and rigorous evaluation of outcomes.

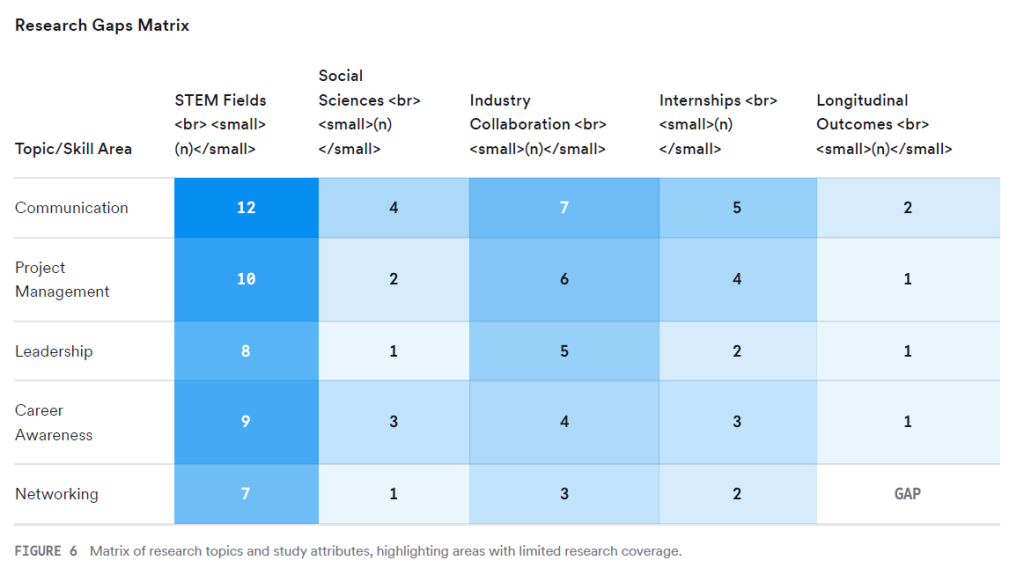

5.1. Research Gaps

Despite substantial progress, research gaps remain in the long-term tracking of career outcomes, the effectiveness of transferable skills training in non-STEM fields, and the impact of such training on underrepresented groups.

Research Gaps Matrix

| Topic/Skill Area | STEM Fields (n) | Social Sciences (n) | Industry Collaboration (n) | Internships (n) | Longitudinal Outcomes (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication | 12 | 4 | 7 | 5 | 2 |

| Project Management | 10 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 1 |

| Leadership | 8 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 |

| Career Awareness | 9 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Networking | 7 | 1 | 3 | 2 | GAP |

Figure 6: Matrix of research topics and study attributes, highlighting areas with limited research coverage.

5.2. Open Research Questions

Future research should address the following questions to further optimise transferable skills training in doctoral education:

| Question | Why |

|---|---|

| What are the long-term career outcomes of PhD graduates who receive formal transferable skills training? | Longitudinal data is needed to assess sustained impact on employability and career satisfaction. |

| How effective are transferable skills programs in non-STEM doctoral fields? | Most evidence is from STEM; understanding impact in other disciplines will inform broader implementation. |

| What interventions best support underrepresented groups in accessing and benefiting from transferable skills training? | Equity-focused research can help ensure all PhD graduates benefit from these programs. |

Figure 7: Key open research questions for future investigation.

In summary, the evidence indicates that formal transferable skills training during PhD programs is a valuable and effective strategy for enhancing graduates’ career prospects outside academia, but further research is needed to optimise delivery and ensure equitable access across disciplines and populations.

References

- Sinche, M., Layton, R., Brandt, P., O’Connell, A., Hall, J., Freeman, A., Harrell, J., Cook, J., & Brennwald, P., 2017. An evidence-based evaluation of transferrable skills and job satisfaction for science PhDs. PLoS ONE, 12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185023

- Roy, D., López, M., & Álvarez, M., 2025. Hires-PhD: a transversal skills framework for diversifying PhD employability. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04257-x

- Lindsey, M., Harris, B., Dahm, L., & Woods, L., 2024. Establishing the short course in transferable skills training program. Journal of cellular physiology, 239, pp. e31324 – e31324. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.31324

- Harris, B., Patterson, N., Williams, C., Gillyard, T., Kirabo, A., Thomas, J., Warrington, J., Cornelius, D., Hinton,, A., Lindsey, M., & Nde, P., 2025. Building Graduate Student Skills and Networks through the SHort course In transFerable skills Training (SHIFT) Program. Physiology. https://doi.org/10.1152/physiol.2025.40.s1.0971

- Woods, L., & Lindsey, M., 2024. Establishing the SHort course In transFerable skills Training (SHIFT) Program. Physiology. https://doi.org/10.1152/physiol.2024.39.s1.897

- Ashonibare, A., 2022. Doctoral education in Europe: models and propositions for transversal skill training. Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education. https://doi.org/10.1108/sgpe-03-2022-0028

- Layton, R., Solberg, V., Jahangir, A., Hall, J., Ponder, C., Micoli, K., & Vanderford, N., 2020. Career planning courses increase career readiness of graduate and postdoctoral trainees.. F1000Research, 9, pp. 1230. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.26025.1

- 2019. Issues in transferable skills training for researchers (Transferable Skills Training for Researchers: Supporting Career Development and Research). **.

- Mitic, R., & Okahana, H., 2021. Don’t count them out: PhD skills development and careers in industry. Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education. https://doi.org/10.1108/sgpe-03-2020-0019

- Salm, E., & McKinney, C., 2024. Design and implementation of a project management training program to develop workforce ready skills and career readiness in STEM PhD students and postdoctoral trainees. Frontiers in Education. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1473774

- Main, J., Wang, Y., & Tan, L., 2021. Preparing Industry Leaders: The Role of Doctoral Education and Early Career Management Training in the Leadership Trajectories of Women STEM PhDs. Research in Higher Education, 63, pp. 400 – 424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-021-09655-7

- Weber, C., Borit, M., Canolle, F., Hnátková, E., O’Neill, G., Pacitti, D., & Parada, F., 2018. Identifying Transferable Skills and Competences to Enhance Early Career Researchers Employability and Competitiveness. **.

- Stamati, K., & Willmott, L., 2022. Preparing UK PhD students towards employability: a social science internship programme to enhance workplace skills. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 47, pp. 151 – 166. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877x.2022.2102411

- Rodrigues, J., Freitas, A., Garcia, P., Maia, C., & Pierre-Favre, M., 2018. Transversal and transferable skills training for engineering PhD/doctoral candidates. 2018 3rd International Conference of the Portuguese Society for Engineering Education (CISPEE), pp. 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1109/cispee.2018.8593472

- Brandt, P., Varvayanis, S., Baas, T., Bolgioni, A., Alder, J., Petrie, K., Dominguez, I., Brown, A., Stayart, C., Singh, H., Van Wart, A., Chow, C., Mathur, A., Schreiber, B., Fruman, D., Bowden, B., Wiesen, C., Golightly, Y., Holmquist, C., Arneman, D., Hall, J., Hyman, L., Gould, K., Chalkley, R., Brennwald, P., & Layton, R., 2021. A cross-institutional analysis of the effects of broadening trainee professional development on research productivity. PLoS Biology, 19. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000956

- 2020. Increasing Employability of Doctorates in Emerging Sectors With Soft Skills Training. **, pp. 45-52. https://doi.org/10.18690/978-961-286-409-5.6

- Martins, H., Freitas, A., Direito, I., & Salgado, A., 2021. Engineering the future: transversal skills in Engineering Doctoral Education. 2021 4th International Conference of the Portuguese Society for Engineering Education (CISPEE), pp. 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1109/cispee47794.2021.9507210

- Miliotis, H., Lee, N., Cayley, R., Zakala, C., Kaplan, A., & Reithmeier, R., 2025. Embedding professional development within the curriculum of graduate programs: An impact survey from biomedical departments in a faculty of medicine. PLOS One, 20. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0321207

- Johnson, E., & Parmenter, L., 2017. Transferable skills for global employability in PhD curriculum transformation. **.

- McGrath, D., Makri, E., Cusack, T., & Mountford, N., 2022. TRAINING IN OPEN SCIENCE FOR PHD STUDENTS: THE STUDENTS’ PERSPECTIVE. Education and New Developments 2022 – Volume 2. https://doi.org/10.36315/2022v2end059

- Steen, K., Vornhagen, J., Weinberg, Z., Boulanger-Bertolus, J., Rao, A., Gardner, M., & Subramanian, S., 2020. A structured professional development curriculum for postdoctoral fellows leads to recognized knowledge growth. PLoS ONE, 16. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.15.340059

- Nguyen, H., 2024. Australian doctoral graduates’ career transition from academia to industry: the PCAP internship competence framework. Studies in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2024.2416492

- Löfflad-Bürkin, B., Matthiä, A., Krasna, H., Künzli, N., Bohlius, J., & Czabanowska, K., 2025. A scoping review of transformational leadership development in health-related PhD programs.. Health policy, 161, pp. 105411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2025.105411

- Meyers, F., Mathur, A., Fuhrmann, C., O’Brien, T., Wefes, I., Labosky, P., Duncan, D., August, A., Feig, A., Gould, K., Friedlander, M., Schaffer, C., Van Wart, A., & Chalkley, R., 2016. The origin and implementation of the Broadening Experiences in Scientific Training programs: an NIH common fund initiative. The FASEB Journal, 30, pp. 507 – 514. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.15-276139

- Brandt, P., Whittington, D., Wood, K., Holmquist, C., Nogueira, A., Gaines, C., Brennwald, P., & Layton, R., 2025. Development and assessment of a sustainable PhD internship program supporting diverse biomedical career outcomes. eLife, 12. https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.91011

- Cui, Q., & Harshman, J., 2023. Reforming Doctoral Education through the Lens of Professional Socialization to Train the Next Generation of Chemists. JACS Au, 3, pp. 409 – 418. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacsau.2c00561

- Ganapati, S., & Ritchie, T., 2021. Professional development and career-preparedness experiences of STEM Ph.D. students: Gaps and avenues for improvement. PLoS ONE, 16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260328

- Claydon, J., Farley-Barnes, K., & Baserga, S., 2021. Building skill‐sets, confidence, and interest for diverse scientific careers in the biological and biomedical sciences. FASEB BioAdvances, 3, pp. 998 – 1010. https://doi.org/10.1096/fba.2021-00087

- Lenzi, R., Korn, S., Wallace, M., Desmond, N., & Labosky, P., 2020. The NIH “BEST” programs: Institutional programs, the program evaluation, and early data. The FASEB Journal, 34, pp. 3570 – 3582. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.201902064